MM 2.2 Implicit Bias v2

In September 2012, Ilana Yurkiewicz reported on a Yale study that analyzed gender bias in the science fields. In the study, scientists reviewed identical resumes for the job of lab manager assistant, half with a man’s name attached and half with a woman’s name attached. According to Yurkiewicz, “Results found that the ‘female’ applicants were rated significantly lower than the ‘males’ in competence, hireability, and whether the scientist would be willing to mentor the student” (Yurkiewicz, 2012).

The surprising outcome to many was that the women and the men showed the same bias. Indeed, it seems quite unlikely that if questioned after, the scientists would say that female scientists were less capable and yet, the perception in this study was that female scientists are less competent and less hireable. The results did not come from overt sexism, but rather from hidden or implicit bias.

Micromessages come from our implicit or unconscious biases—social stereotypes that we form outside of our own consciousness. These biases stem from our brain’s tendency to organize information by setting up “filters” to categorize what we observe to make sense of complex situations. They present barriers to equitable treatment in the classroom and impact how we relate to people and our assumptions about them.

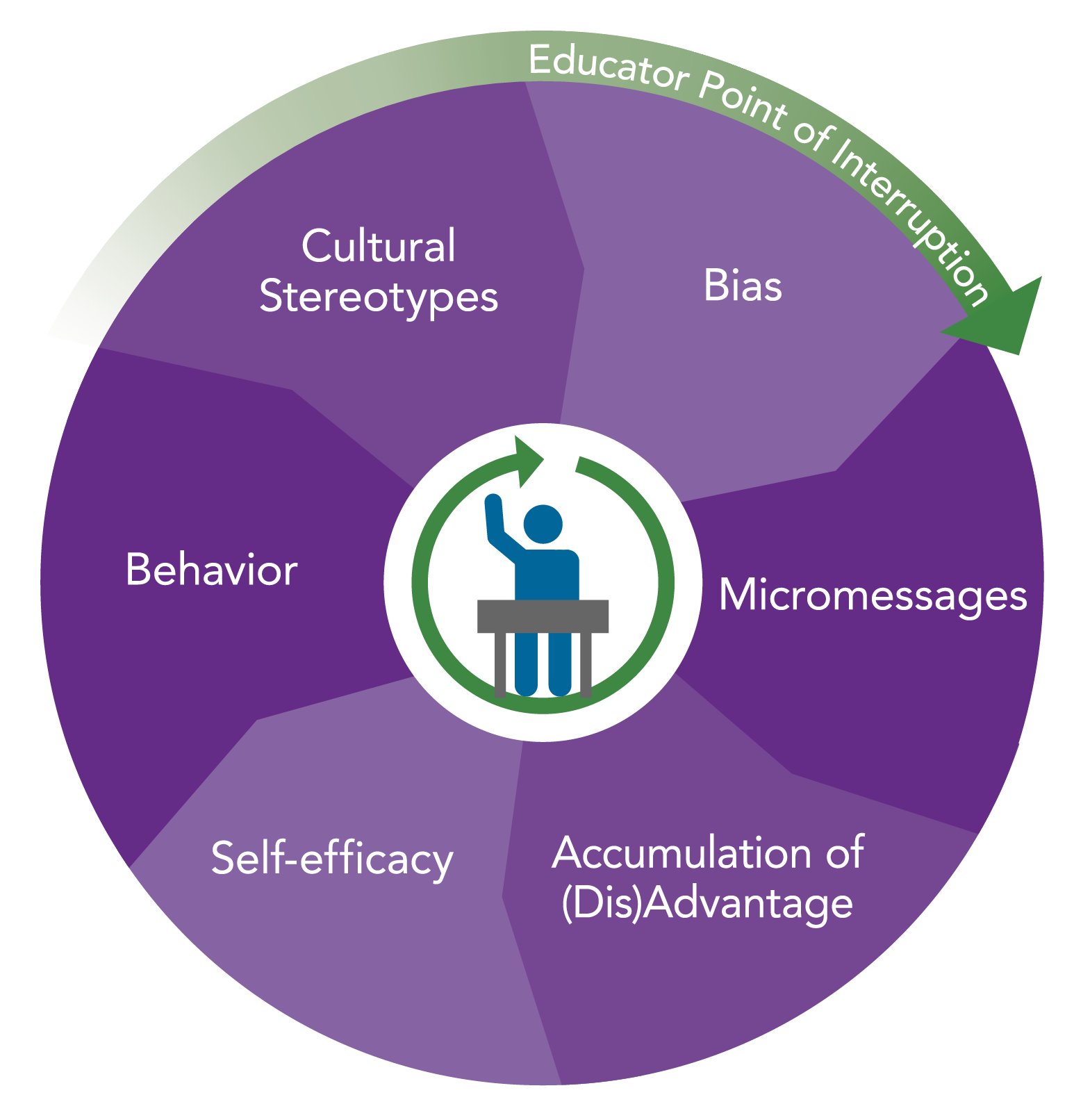

A number of mutually reinforcing factors are at play in the transmission and reception of micromessages:

Figure 1: NAPE Culture Wheel

Based on the work of Bernice Sandler, Mary Rowe, and the American Association of University Women (AAUW). Published in Morrell & Parker (2013).

Stereotypes or beliefs we hold within our culture lead to biases of which we are often unaware. Bias can be explicit or implicit. Explicit biases in education are mostly illegal today, thanks in part to Title IX, but also because of our changing culture. Implicit biases remain because we as educators may inadvertently hold stereotypical beliefs that feed the micromessages we may be sending.

As the micromessages accumulate over time, they affect the receiver’s sense of self-efficacy (Rowe, 1990). Self-efficacy is one’s belief in one’s ability to produce an outcome, reach a level of performance, or achieve a goal. The receiver’s self-efficacy affects her or his behavior, which then further reinforces the stereotypes and beliefs.

If we want to break the cycle of negative stereotypes, we need to interrupt the transmission of micromessages.